We’ll return to Carrie and Delia Wood, but first, I want to tell another story.

This is the story of a woman called Pamela by her enslavers but who remembered her parents, in her youth in Africa, calling her Loquassichub Um. We tell her story at the house museum where others were sheltered and aided on their way to freedom via the Underground Railroad. But the man who eventually set her free, Rev. Jonas Meriam, was also the father-in-law of John Kenrick, Esq., whose stories we tell at our other house.

Francis Jackson, 19th century chronicler of Newton history, writes:

“After [the reverend’s] marriage to Miss [Jerusha] Fitch, her m[other] came to reside with them at Newton, and brought with her a female slave, named Pamelia (sic), whom she received as a present from her s[on] Eliphalet Fitch, Esq., then residing on the island of Jamaica; the treatment of which slave, by her mistress, sorely troubled Mr. Meriam. One day, on seeing his m[other] in law strike and otherwise maltreat the slave, he asked at what price she would sell her to him; she replied, ‘one hundred dollars.’ He immediately paid the price, and thereupon gave Pamelia her freedom; but Pamelia chose to reside with him, and did so until his death, in 1780, after which she went to live in Little Cambridge, [Brighton], where she m[arried], and d[ied] a few years since, at very great age. Pamelia often said that she was born in Africa, and was called by her parents Loquassichub Um, and that she was stolen from her parents when a child, and carried to Jamaica, where she became the property of Mr. Fitch, who brought her to this country and gave her to his m[other], while on a visit here.” (p. 367)

Francis Jackson goes on to cite the Rev. Meriam’s grandson, born of his only daughter, as the source for the story. Rev. Meriam’s only daughter (with his first wife, Mehitable Foxcroft) was Mehitable Meriam, who married John Kenrick, Esq. Thus, the source of the story would have been William or John Adams Kenrick. But something about the story always bothered me. It seemed a little too white-knighty. And in fact, Jackson continues:

“Wheresoever the gospel of humanity shall be preached or written, such acts as this will be remembered as long as the act of ‘breaking the alabaster box of precious ointment upon the head of Him who came to open the prison door and set the captive free.'” (p. 367-368)

So I started digging. Because wills are often one of the best available sources for determining what happened to enslaved people, I started there. First, I looked at Jerusha Boylston Fitch, the mother-in-law in question. She died in 1799, having outlived both her daughter (died 1775) and son-in-law (died 1780). I confirmed her will didn’t refer to Pamela (shouldn’t have!), so I went to check Jonas’s will — it also made no mention of her. So far, this was arguably consistent with the story, even if it didn’t do anything to actually prove it.

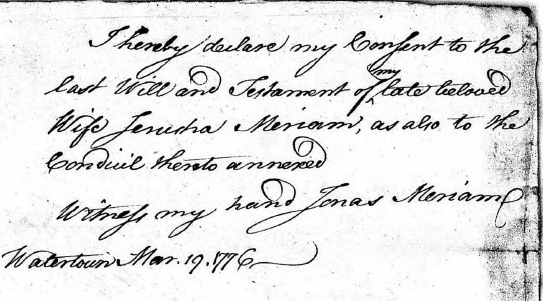

Then I noticed that Jerusha Fitch Meriam had also made a will. This was unusual for a married woman who was not a widow (as her mother was), but not deeply so, as she was from a decently well-off family and had been her husband’s second wife. Her probate actually included a statement from Jonas:

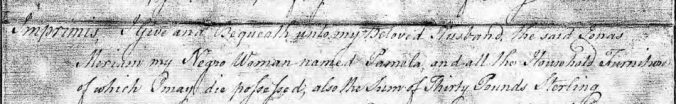

And then I found this:

If Jonas bought her from his mother-in-law after watching an intolerable beating and freed her on the spot, she would not have been Jerusha Fitch Meriam’s property to bequeath. White knight officially slain.

But the rest of the story — that, after being given her freedom by Jonas (whenever that was), she remained with him until his death — actually does seem supportable and would have been consistent with the experiences of many enslaved folks “freed” into “servancy” in the years between the Revolution and turn of the century.

Jonas died on 3 August 1780, and his will was written that spring, a few months prior. The lack of any reference to Pamela suggests she was free by then (and that he didn’t choose to provide for her, but that’s a separate matter). The story also said she married, so I went looking for her happy ending.

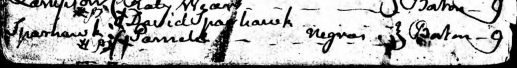

On 9 August 1780, just six days after Jonas’s death, this marriage intention was filed in Boston:

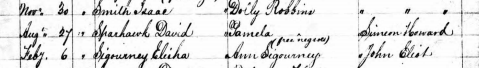

And on 27 August 1780, they were married:

I haven’t yet found either’s death/burial records, but their marrying so quickly after Jonas’s death and the fact she wasn’t mentioned in his will written some months prior tell me she was indeed freed (and began her relationship with David Sparhawk) before Jonas’s death. A little girl kidnapped from her family finally had self-determination and, I hope, happiness.

Rest in Power, Loquassichub Um Sparhawk. You survived.